Ein Beitrag von Emilia Roza Sulek

There are moments in every scholar’s life, when one accidentally opens a computer file with a title which does not say much about whether it is a draft of an article, a half-translated interview or an unfinished application. These pieces of writing were abandoned as our writing zeal declined, when other tasks came in the way, or when interests changed. If authors before had a drawer where they would dump such drafts while cleaning the desk for something more urgent or important, nowadays the folders in our computer play such a role. Some of these forgotten pieces of writing are accidentally deleted during some upgrading process or get lost while changing the drive and other devices. Some do not even leave a trace in our memory. With some files, we regret losing it, like I do, of an interview with an elderly nomad who told me of his youth spent as a bandit and of his prison term served for stealing Ma Bufang’s horses. I had few of such confessions.

Much of the aborted writings which survived computer purges are never used for publications, because we either need additional data or the topic does not belong to the main field of our expertise. Although we consider these pieces of writing as ‘too short’ to publish, they contain interesting data. As field researchers, we have access to a wealth of information which we receive aside our main inquiries. These pieces of information can be useful for other people, scholars and non-academic readers. However revealing or inspiring such information can be, it sometimes disappears in an abyss which opens up between academic writing where ethnographic data should illustrate a theoretical debate or support a grand thesis and writing for popular journals, which is not easy to produce for scholars and is ruled by its own laws of what an attractive read is or not. This ‘abyss’ absorbs large parts of what the researcher hears, observes, and notes down in the field. Yet, accidental discoveries of our forgotten computer files can sometimes give such material a second life.

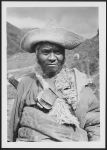

The text below is an interview with a singer whose music accompanied me during my field research and whose songs were played in restaurants, shops and cars. The genre called dunglen, which he mastered, is performed with the accompaniment of a mandolin and dunglen lyrics often originate from folk songs. Yet, in present-day Tibet, the lyrics often venture into new, political or socially engaged fields. The reason I conducted this interview is connected to this. The singer was well-known for his critique of certain aspects of social and economic life which he expressed in his songs. Besides, I was a fan of him. Although I am an anthropologist and he was my informant, this was an interview with a celebrity. My informant did not appear in tabloid newspapers because such newspapers did not exist in his region, but he was nevertheless on everyone’s lips. His special status was magnified by the fact that he had been detained during a wave of preemptive arrests that swept through his region before the Beijing 2008 Summer Olympics. It was common knowledge that the arrest was not his first time.

The interview was planned for a publication in a journal, but I never managed to finish it. Conducting an anthropological and journalistic style interview are two different things and I was not sure what story to tell. I planned another meeting to continue talking with him, to get a proper photograph taken of him, and so on, but none of these happened. Below are parts of an edited interview. They will never become part of any academic publication (at least not mine), and the chance that we meet again to finish the interview is small. That would anyway be a meeting of two different people, different than in 2009 when we met for this interview.

Continue Reading →